Jennifer Brazelton: Essential

Structures

I juxtapose the macro and

the micro to highlight visual parallels and to remind us that we are

structurally connate with the world around us.

Relationships and interdependence are building

blocks for Jennifer Brazelton’s work. Her

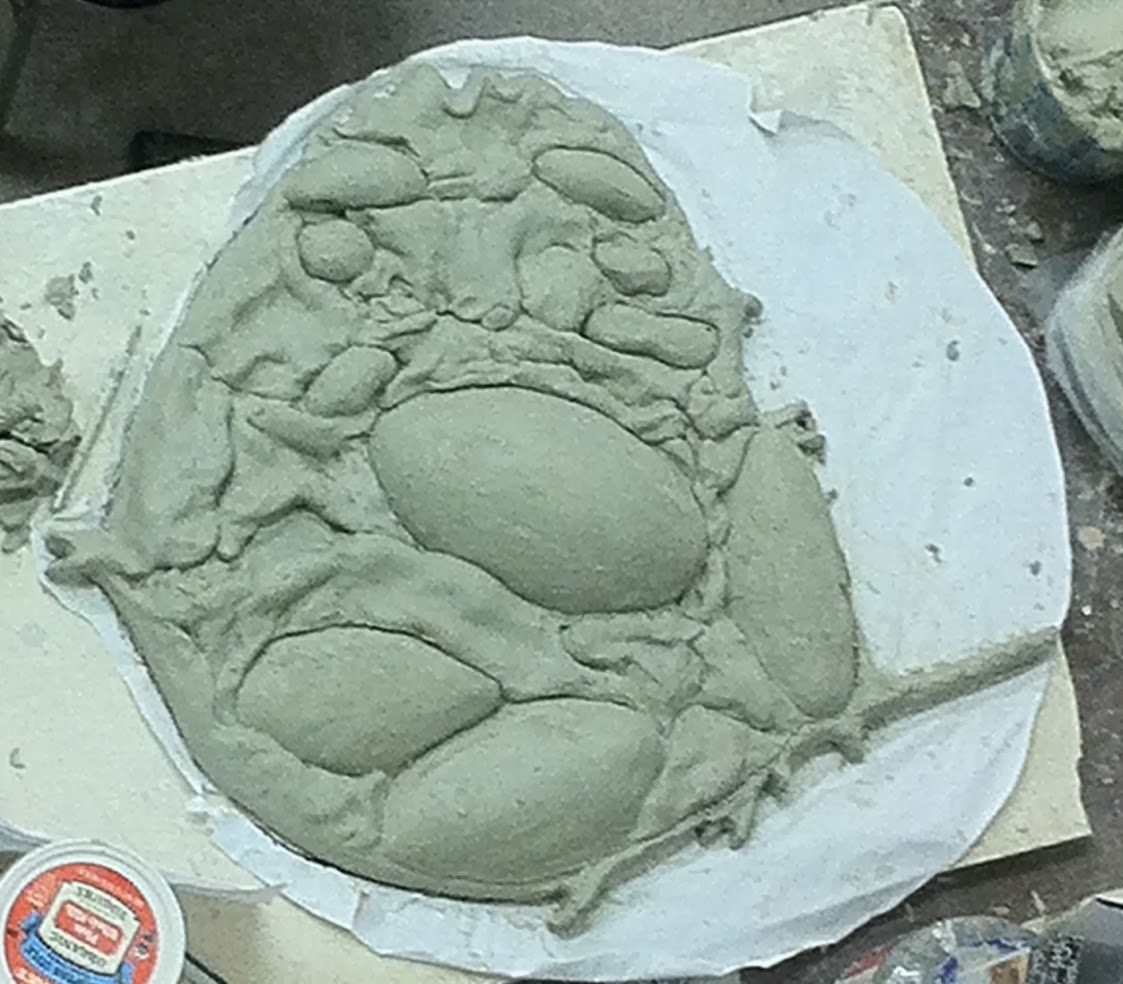

intricately constructed ceramic forms re-present and abstract our daily

environment. Using extrusions and pressmolds to generate mass-produced parts,

she arranges multiple elements in layered, formal relationships. The work is simultaneously apprehended as

convoluted highway ramps and as Petri dishes.

Our human point of view oscillates wildly. Are we inside it or outside

it? Governed by it or controlling it?

Brazelton

describes herself an abstract artist. To abstract is to summarize, express a

quality greater than individual elements; to look at ideas. But how do we look

at an idea? In our increasingly sophisticated world, bombarded with visual

signals, Brazelton’s approach utilizes common practice. The artist employs

abstraction by visual blurring between very large and very small points of

view. Repeating patterns - bacterial colonies or farm fields - show an

arrangement of orderly elements whose purpose includes generation, protection

and nurture. Brazelton reduces these

components to reveal essential elements of the governing structure.

Her inspiration comes from visual patterns as

apparently unlike as maps of San Francisco bus lines, viral colony growth

patterns, or machine gears. Patterns of the urban environment contribute to her

organizing principles of visual composition. The mechanical formations hide the

hand of the artist. What is revealed is the mind of the artist.

This intensive investigation

began during graduate study at San Francisco State University. For her thesis exhibition, Brazelton took the

view from a plane as her point of departure, creating scaled landscapes of

fields and cities as seen from the sky. Relationships of size and space,

especially hidden aspects, change with distance. The abstracted perspective

which allowed new visual relationships to emerge intrigued the artist, who

says, “Long airline flights provided

inspiration in the ever-changing landscapes…layered over each other. Rivers and roads became branching trees,

human veins, and knots of rope.”

Brazelton’s highly

thoughtful work includes installation and social practice, such as Pieces of What, a large-format work

recently exhibited at the Richmond Art Center. The wall-mounted piece is a

complex pattern of circular blue forms, with irregular interiors in formal

shapes suggesting a labyrinth. Viewers experienced a focusing of vision, from

the large view across the gallery to face-to-face inspection of color and

texture of individual components. Brazelton says: ”Color for me expresses emotion/ texture can suggest many

things simultaneously.” The composition evokes a map, with implied movement, pathways and

destinations, and the dissected tubular forms reference the human lymph system,

called a transport system in

medicine.

The Lamentations

series critiques the American practice of war as business. War has changed very

little for soldiers at the human level, even as weaponry has moved from stones

to smart bombs. This is the aspect that Brazelton addresses. What is war? is it

the nightly news? The body count, which was dinnertime viewing fare during the

Vietnam era? Lamentations: Growing

American Culture resembles a giant sunflower. Very close reading reveals

that the ‘seeds’ are hundreds of tiny heads of soldiers in helmets. The generic

little heads call up our tepid reaction to the newspapers listing their deaths,

where each face receives one square inch of newsprint in a format as ultimately

anonymous as Brazelton’s minute castings.

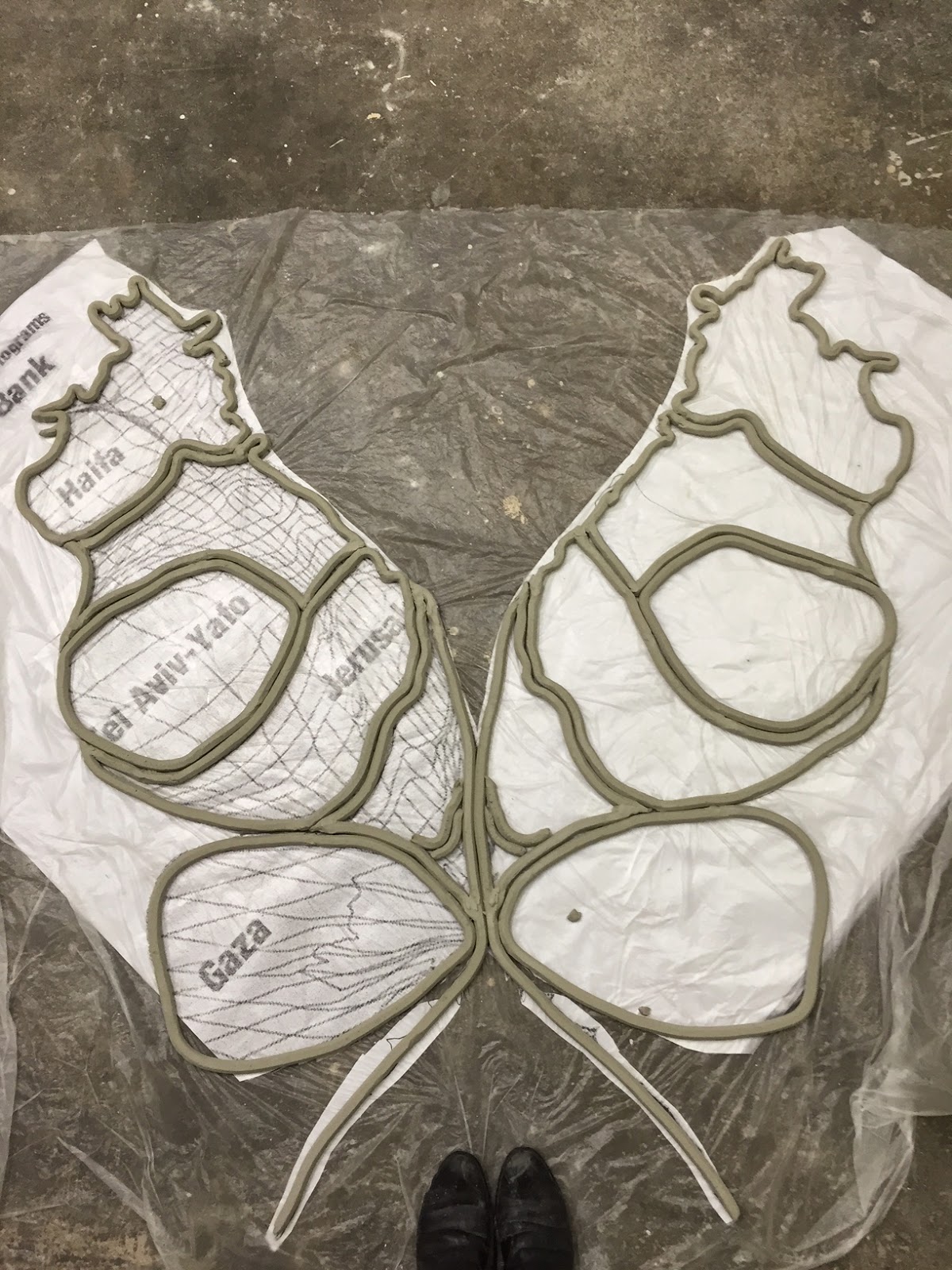

Brazelton’s

Neighborhood series looks at the

gated community concept in terms of organic generation and protection. Much

map-based art uses the original cartography, altered but still inherently

familiar at a casual read. Brazelton further abstracts this, remaking the world

in terms of the connection between a baby’s head and an electronic

gatepost.

Neighborhood: Crossroads is an attenuated oval shape

with three swelling apertures, symmetrically placed around a saw-toothed red

form. The color of the red form, its shape and the texture of the wet red glaze

all evoke organic growth. Small spurs on the edge of the red form reveal

themselves, on close reading, as baby heads. They are slick and mottled with

red, like newborns. At the core of these

implied lives is the nurture and

protection of the babies inside the gates.

Very real human conditions drive families to choose survival and

guaranteed protection through such exclusivity. Today’s most exclusive retreat

in the world is found in the manufactured islands near Singapore, quite

literally a world of one’s own, which is what Brazelton asks us to consider.

Aerial views of these new constructions bear an uncanny resemblance to

Brazelton’s clay communities.

Brazelton’s process, like the work she creates, is

an intricate layering of intimate and monumental structure, fused into a new

entity. She says “My

creative process is about absorbing and filtering ideas and information.”

It

is important to the artist that the works are beautiful, and that they meet

exacting standards of technical construction and formal composition. In order for the close relationships between

macro and micro structures to prove out, they must be accurately made. The

necessity for getting all the details right at this level makes Brazelton a

meticulous worker. Although her careful attention to detail is thorough and

considered, she remains open to spontaneous evolution, and the clay contributes

its unique unpredictability:

“I love the unknown element, especially the results of kiln firings. You

might think you know what is going to happen, but often it is not what you

expected. This can be both good and bad.”

Brazelton

uses abstraction to reveal hidden structures stripped of nonessential elements.

Engaging her detailed work is provocative, as we are called upon to exchange

casual perception for a thorough awareness of how closely enmeshed we really

are. To be connate can indicate that dissimilar elements are forced together.

The layers of such connate structures vary extremely: water in rock, charged

ions in soap, soldiers at war. The protected family inside an exclusive

community is also confined there, linked through social expectation and

practice. Brazelton’s ceramic works

locate and examine these hidden relationships, creating a fascinating new

lexicon.

Jennifer Brazelton’s

work is exhibited nationally and appears in numerous publications. She maintains her studio at the Voulkos Dome

complex in Oakland and teaches at California State University, East Bay,

Merritt College, Ohlone College, and San Francisco State University. Brazelton

lives with her husband, artist Tom Michelson, in San Francisco.

Susannah Israel is a

well-known artist, writer and educator living in East Oakland. www.SusannahIsrael.net